We seldom witness, through global media, an everyday incident that instantly moves massive numbers of people to outrage and protest.

But, around the world, that’s what has happened in recent weeks.

The police killing of George Floyd, an ordinary middle-aged African American, in Minneapolis should not have seemed remarkable. After all, police in the United States routinely kill about 1000 citizens annually, a disproportionate number of whom are black and Hispanic Americans.

Any killing of a human life should attract attention, but when it becomes an everyday happening, our responses become immune.

The pent-up tensions among black Americans towards racism and institutional brutality has been simmering and boiling for as long as the country has existed. Add in the collective anxieties of a country besieged by a pandemic and dysfunctional leadership, and we see the ingredients for foment.

But that alone does not quite explain why this explosive outpouring of outrage, not just in the US, occurred. Black people have been killed, lynched and choked to death many times before. “I can’t breathe” was murmured by another police victim, Eric Garner, less than a decade ago.

If Floyd had been gunned down in cold blood, the facts alone might not have moved many to protest, especially if it was merely a news report and there was no video or photographic evidence. Moreover, have not we seen people gunned down a thousand times in movies and on television to the point it has lost its shock value.

Somehow, the video of the cop pinning the man down struck a particular reaction and people could see the brutality of it. It became personal.

George Floyd – a grandfather and sports-loving giant of a man – died slowly and with an apparent absence of drama. The cop simply had him immobilised and pinned him down with a heavy knee to the neck for nearly nine minutes while the helpless man’s life ebbed away. Some bystanders offered protest and Floyd informed the cop, “I can’t breathe”.

We can each best explain our own outrage by examining our personal reaction. The long, slow and passive murder of a man immobilised on the ground, with hands cuffed behind his back, is the stuff of nightmare. We feel his pain. For some it’s likely to be a recurring dream, especially for those, like Floyd, who understood and feared the ever-present threat of attack by law enforcement officers.

The deprivation of mobility and of life-giving air equates to the denial of basic human rights that institutional racism visits on many people around the world. This is not just an occasional mindset for many people, it is an ever-present reality of life. So, for those who don’t experience this, they could now see the terror of it and relate to it personally.

In my professional life as a communicator, I have sometimes used a question to explain the powerful forces of an emotional response. The question is: “Why would any sane person rush into a burning house, even if it could mean death or serious injury?”

The answer is: “Because the person must save a child.”

Now, ask that same question with the possibility that a bag with a million dollars is in the burning house? Most people would have to stop and weigh whether loss of life is worth gaining a million dollars – a rational, rather than emotional choice.

People in the US protested in their thousands without thinking about the threat of Covid-19 or retaliation by the police. They were prepared to risk anything, even their lives, because they were outraged by the situation, and the personal emotions they felt. It would have been even easier for those who felt they had nothing to lose anyway – black and marginalised people. All were hell-bent on getting justice and changing things for the better.

There is surely a useful lesson in all this. The world is full of injustices and problems, from inequities and pandemics, to the state of the environment. Facts and statistics inform us, but they rarely move people to take affirmative action.

It’s a fact that a scene of hundreds of starving children in Africa will fail to move many people to donate to help them. A photo of a single starving child with tears in their eyes snaps many to action. It’s because it’s personal.

You can contact Fraser here.

You can contact Fraser here.

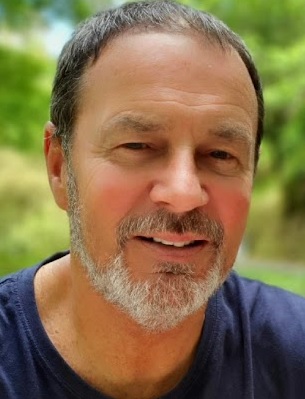

Fraser Carson is the founding partner of Wellington-based Flightdec.com. Flightdec’s kaupapa is to challenge the status quo of the internet to give access to more reliable and valuable citizen generated content, and to improve connectivity and collaboration.

Flightdec websites include: KnowThis.nz, Issues.co.nz and Inhub.org.nz.

OTHER POSTS

LATEST POSTS

- Fear breeding fear, fear and more fear

- Poor official communications fuel misinformation

- Cultural infrastructure could be our saviour

- Four-storey blocks coming as developments fast-tracked

- The world’s therapist offers little hope for global ills

- Modern conservatism the quiet killer

- However bad it might get, keep smiling

- AI is coming, ready or not

- Arise King Brown of the Kingdom of Auckland

- Rebuilding should draw on mātauranga

- Brown hits the fan as water levels rise

- When small stuff becomes really big stuff

- Unfettered lies and misinformation threaten us all

- Misinformation, crime and political shenanigans

- A vote for me is a vote for nothing

- Enduring the tough life of homelessness

- A time to reflect on local politics

- It takes a village to raise a child

- Reclaiming lost traditions

- A test for democracy at Ōtaki College