Has there been a time, in the past 100 years, when democracy as a cornerstone of society has been so globally threatened as now?

Putin’s incomprehensible invasion of Ukraine, Trump’s gross attempts to subvert the United States electoral system and Boris Johnson’s casual corruption likely take us back to the 1930s for any kinds of a parallel.

It perversely reminds me of something in my own dark past that plays a part in forming my views on authority and the role of democracy and citizens in decision making.

In the dimming light of my time as a student at Ōtaki College, a small number of us students plotted a regime overthrow. Well, that might a be a tad exaggerated, but it was never-the-less schemed with the same gaze as one can imagine Hōne Heke plotting the demise of a flagpole at Kororāreka or Guy Fawkes’ plan to blow up the House of Lords.

Among the student body of 1972, trouble brewed in some quarters. Unrest had been marinated by the daily news diet of the Vietnam War and other global unrest, and some in our baby-boomer generation sensed power transferring to younger shoulders.

The playground issues in the school were minor in comparison, but none-the-less embraced feelings on inequity and unfairness, arbitrarily handed down by authorities, some of whose stature was much shorter that us. Issues fermented, such as indiscriminate caning of male students and student uniforms that were inadequate for winter conditions. But mostly, it was simply a plea for the students to have some kind of voice in decision making.

So, back to our student plot to blow up the House of Lords. We decided to set up a student body (Ōtaki College Student Council) that would meet monthly, with members elected from classes. I offered myself as chair and proceeded to preside over the systematic dismantling of all school authority.

The long list of demands, captured from each meeting, fell to me to write into a standard Collins A4 notebook, and plod along to the principal’s office for immediate remedy. It was a screaming success (the notebook and principal’s office) except that we achieved absolutely zero. Zilch!

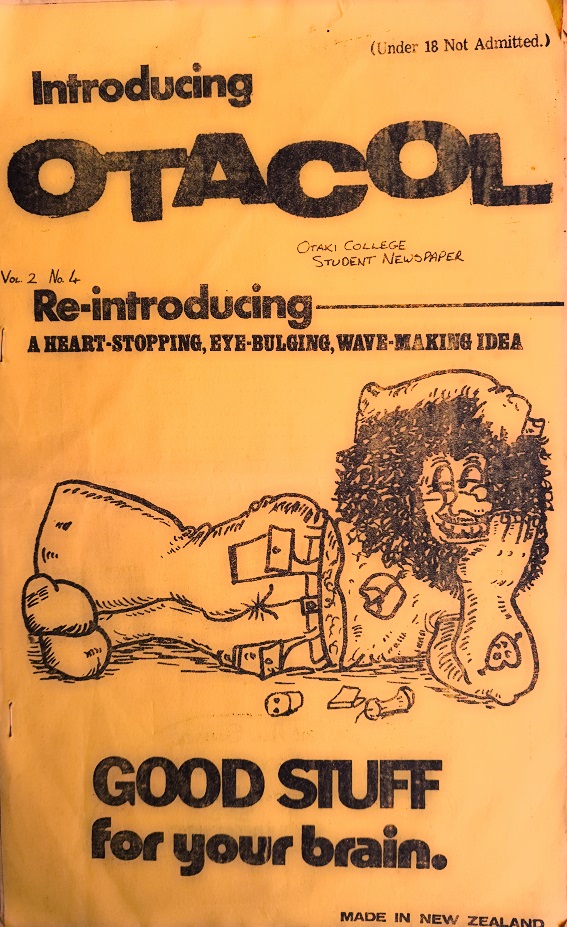

Volume 2, No 4 of the 1972 Ōtaki College magazine, Otacol. The student publication, based on radical university magazines of the time such as Salient and Cracum, provided a voice for college students that was not being heard by the college management.

Fraser Carson collection

Then, with a bit of whispered encouragement from a few staff members, we cunningly set up a student newspaper called Otacol, which I edited. That way, the student council (chaired by me) could present the list of demands and Otacol (edited by me) could favourably report on such proceedings.

It was, of course, corruption on an industrial scale – akin to Jacinda taking over the editorship of TV One News and RNZ, or Guru commandeering this newspaper.

However suddenly, with each Otacol edition, there was some progress. “Selected” students were invited to discussions with the school management and there was some movement on issues, with a promise to keep dialogue going.

If there’s a lesson in this, apart from the inadvisability of Soviet-style monopoly control of politics and media, it is this. A genuine citizen’s voice, as an input into decision making, is essential in a healthy society. But it’s generally not sufficient for groups to take a position in isolation, as our student body did. There needs to be clear channels of communication that lead to connectivity and the building of mutual trust, otherwise progress is likely minimal, or groups form as isolated fiefdoms that might assert pockets of power but have limited community-wide benefits.

In this column I’ve frequently written about “community building” as a way of re-establishing a coherent and robust civil society.

It’s important, even though these are broad-brush and quite highfaluting notions. But there’s nothing new about it – it’s just that we seem to be slipping into the abyss of individualism and divisiveness, over collectivism, which is actually what democracy is about – the will of the majority.

No democracy can be perfect, but it’s the best thing we have, and we should protect it with all we have.

You can contact Fraser here.

You can contact Fraser here.

Fraser Carson is the founding partner of Wellington-based Flightdec.com. Flightdec’s kaupapa is to challenge the status quo of the internet to give access to more reliable and valuable citizen generated content, and to improve connectivity and collaboration.

Flightdec websites include: KnowThis.nz, Issues.co.nz and Inhub.org.nz.

OTHER POSTS

LATEST POSTS

- Who was our first knight?

- Carl Lutz – farmer who loved the land, and Fordsons

- Money for the expressway – for whom does the bell toll?

- Arthur saw nature ‘with eyes of admiration’

- Ōtaki-Māori Racing Club ‘focused on mana and mauri’

- If you’re not there you won’t know what’s going on

- Ōtaki abuzz with film festival - Ōtaki Today

- Hall helps to connect and build community

- Fear breeding fear, fear and more fear

- Plenty of help organisations in times of need

- Poor official communications fuel misinformation

- Cultural infrastructure could be our saviour

- Four-storey blocks coming as developments fast-tracked

- The world’s therapist offers little hope for global ills

- Modern conservatism the quiet killer

- Di’s QSM for services to community and environment

- However bad it might get, keep smiling

- AI is coming, ready or not

- Rewi’s story one of adversity in old Ōtaki

- Arise King Brown of the Kingdom of Auckland