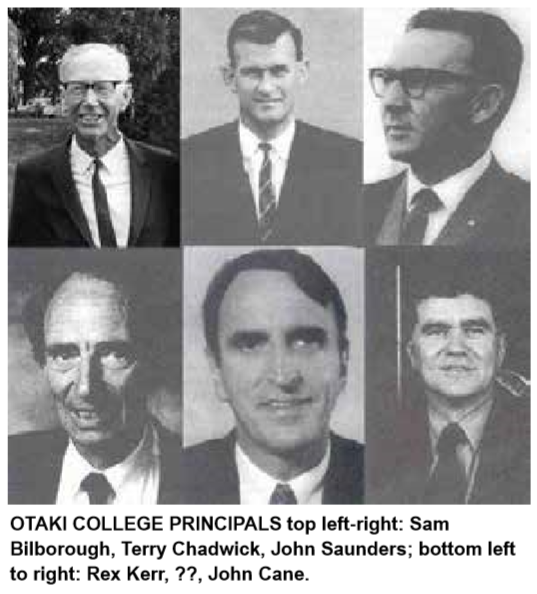

By Rex Kerr, principal, 1976-97

The early years of Ōtaki College were a time of relative stability and consolidation, with the roll growing to 603 by 1976.

The early years of Ōtaki College were a time of relative stability and consolidation, with the roll growing to 603 by 1976.

The following years were a time of constant change. The roll increased further in the 1980s to just over 680, then dropped to hover about 500. The baby boom was over.

With the loss of students, staffing numbers also fell, but the percentage of Māori gradually rose from 20 to 40 percent. The curriculum had to meet changing student needs.

Te reo Māori was introduced in 1977 and the arrival of Hiko Hohepa in 1978 saw it flourish, along and with the introduction of day classes for adults. There was a renaissance in te reo locally. For three years in a row, Ōtaki College had a representative in the Pei Te Huranui Jones National Whaikorero finals with Mauri Ora Kingi winning in 1979 when Ngāti Raukawa and Ōtaki College hosted the finals in Ōtaki. Te reo went from strength to strength with the arrival of four prefabs to house the newly established bilingual unit, which later developed into an immersion unit.

In 1978 the first of a series of national reports, the Johnson Report, came out decrying the fall nationwide in national standards, and the basics in particular. A guidance counsellor was appointed in 1979 and as the roll grew new subjects such as Japanese were added to French and Māori. Horticulture was added with the opening of the horticulture block in 1981.

Work transition was introduced in 1978 for students looking to take up apprenticeships, and in 1987 Ōtaki College became a targeted school. During this period the old Endorsed School Certificate was replaced by Sixth Form Certificate and non-University Entrance subjects, such as physical education, computing, business studies, and design and technology, were added to the curriculum.

Change accelerated in 1987. Ōtaki College was a selected school for the National Building Code Survey and the National Curriculum Project, and to top it off the Picot Report came out, which brought huge changes with Tomorrow’s Schools in 1989.

This placed enormous pressure on the college community. The board of governors was replaced by a board of trustees – appointed representatives of the PTA, borough council and Education Board were replaced by elected parent representatives. The new boards were given greater authority over the running of schools, including finance, buildings, staff appointments, local curriculum and policy development.

The principal and staff were given greater responsibility for the day-to-day running of the college and curriculum delivery. Principals became CEOs and advisors to the trustees. Changes came elsewhere – education boards, regional offices, the inspectorate and examination boards were abolished and replaced by the Education Review Office, NZ Education Qualifications Authority and a smaller Ministry of Education.

Charters and a plethora of policies were required to meet every contingency, including teacher development and supervision, student safety, and curriculum delivery and implementation. As these administrative changes were being absorbed, Ōtaki College took on new challenges. In 1991 the school went into partnership with Wellington Teachers’ College and Ngāti Raukawa, and established a Māori language teachers’ outpost, Te Whanau o Akopai ki Te Upoko o te Ika. The following year, the Weraroa Unit was set up for severely disabled students.

Despite the extra load imposed on the whole school, sound, productive teaching continued and students did well. Examination passes were above the national average and in most cases above 75 percent. In some years, bursary passes were as high as 100 percent. Several students went on to earn scholarships to study in Canada, Japan and Australia.

In the early years many students left aged 15, went straight into work and progressed to become successful businessmen and women in a wide range of trades and activities. Others went into the armed forces to rise through the ranks to senior positions.

Chinese students made up 5 percent of the roll and were great achievers, most going on to university and the professions.

Extra-curricular activities, cultural interests and sport thrived. Outdoor education was available to all students and a wide range of camps were organised, depending on student needs and interests, and staff expertise. These included camping, tramping, cycling, canoeing, sailing, skiing and fishing.

Cultural interests were not ignored – kapa haka, choral, orchestral, band, bell ringing and debating were available to students and involved inter-college exchanges. Students were given opportunities in a wide range of summer sports, including athletics, canoeing, cricket, equestrian, softball, swimming and tennis, and in winter basketball, hockey, netball, rugby, soccer and volleyball. Students went on to represent New Zealand at senior level in eventing, canoeing, basketball, kayaking, rugby league and rugby, with John MacDonald representing New Zealand at the Seoul Olympics in kayaking. The most eagerly anticipated events were the overnight school exchanges with Taihape, Queen Charlotte and Okato colleges.

The annual visit by the Ōtaki Scholar from Robert Gordon’s College in Aberdeen was a highlight. The rural character of the college was seen through activities such as the lamb and calf day and the whole-hearted involvement of parents, staff, students and board in the annual gala.

None of these successes would have been achieved without the commitment and dedication of enthusiastic, competent staff members to a heavy teaching load, and their involvement in the extra-curricular programme.

LATEST POSTS

- Carl Lutz – farmer who loved the land, and Fordsons

- Arthur saw nature ‘with eyes of admiration’

- Ōtaki abuzz with film festival - Ōtaki Today

- Hall helps to connect and build community

- Plenty of help organisations in times of need

- Di’s QSM for services to community and environment

- Rewi’s story one of adversity in old Ōtaki

- Urban designer poses critical question - What’s the plan for Ōtaki?

- New road evokes memories of apples and steam trains

- A slick and shiny surface signals a ready expressway – almost

- Black ferns 10, NZ Rugby 0 – no contest!

- Let’s think outside the box to solve town’s problems

- A full life for proud dad Sam Doyle

- Helping navigate the crossroads of people’s lives

- Ōtaki could be even greater, if by design

- Achievements Celebrations

- Active Recreation

- Agriculture

- Arts Culture

- Business

- Children

- Come To Live Here

- Come To Visit

- Commemorations and Reunions

- Community

- Community Action

- Community Development

- Community Resilience

- Community Services

- Complaints Protest

- Eco Environment

- Education

- Family

- For Kids

- Health

- History Legacy

- Housing

- Infrastructure

- Kindness Respect

- Local People

- Local Political

- Obituaries

- Older People

- Perspectives

- Political

- Recognition Awards

- Safe Behaviour

- Safe Communities

- Spirituality Religion

- Sport

- Stories About People

- Town Environments

- Transport