Local historian REX KERR continues the story of how the natural phenomena have shaped Ōtaki’s landscape. This is episode 4, part 1 of “Other forces come into play”..

In 186AD a violent eruption of huge magnitude occurred in the Taupō area.

It’s considered to have been one of the largest eruptions anywhere of the past 10,000 years, producing more than 50 cubic kilometres of ash and debris, and destroying more than 20,000 square kilometres of the North Island.

Taupō has a history of violent destructive eruptions. One of the largest to occur anywhere was 22,600 years ago, which produced 1170 cubic kilometres of debris. Some of the ash carried as far as Ōtaki and left a thin layer deposited on the high country.

The immediate impact of the 186AD eruption on the Ōtaki district was not directly from the eruption, but from an associated source.

The explosion deposited up to 50 metres of debris over the Central North Island, clogging the rivers that had their source in the volcanic plateau. This debris was then washed in vast rafts of pumice down the Whanganui, Whangaehu, Turakina, and Rangitikei rivers and carried out to sea.

The prevailing north-westerly winds and South Taranaki Drift carried it south in huge amounts, which was deposited on the emerging coastline from north of the Rangitikei River to Paraparaumu. As accumulations of sand were built up along the shoreline they were blown inland in huge drifts reaching their greatest extent at Himatangi, penetrating more than 12 kilometres inland and more than 100 metres high.

Further south around Ōtaki, the dunes drifted inland several kilometres, burying the existing features under hills of sand as yet unnamed.

Between the dunes there were areas of swamp and wetlands. South of Te Horo they buried the Te Horo Cliff. Today the motorway construction at the new Waitohu Overbridge and at Hillcrest has revealed the size and extent of these old dunes.

Another impact of these migrating dunes was to block the courses of smaller streams leading to the sea, forming a series of small lakes from Whanganui to Paraparaumu. Like the dunes they are as yet unnamed.

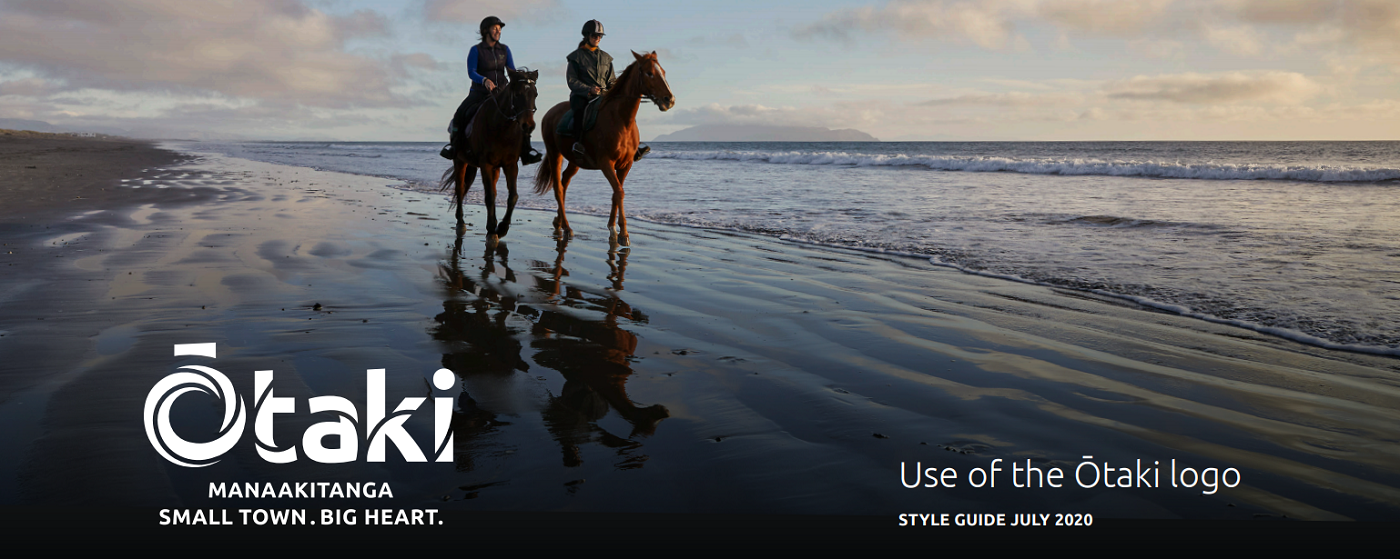

Many of the smaller lakes have long disappeared, to be marked today by areas of swamp or wetland. The West Coast’s long flat distinctive black beaches stretching from Whanganui to Paekākāriki reflect the iron present in the pumice.

The beach is still being replenished today by coastal drift, tidal surges, storms and floods.

References:

- Fleming, C A. “The Genesis of Horowhenua.” Weekly News, Christmas edition. 1961.

- Begg, J G & Johnston, M R. Geology of the Wellington Area. Institute of Geological & Nuclear Sciences Ltd. Lower Hutt. 2000.

Next episode: Other forces come into play continued. Part b: Earthquakes have an impact.

LATEST POSTS

- Who was our first knight?

- The doctors and hospitals that shaped Ōtaki

- How out-of-work men cleared Hautere

- History milling around

- Medals tell a story spanning the world

- Carl Lutz – farmer who loved the land, and Fordsons

- Claimants lament loss of Rangiuru Pā

- Medal for Roy after nuclear test service

- Arthur saw nature ‘with eyes of admiration’

- From whaler cottages to Airbnbs

- Ōtaki abuzz with film festival - Ōtaki Today

- Hall helps to connect and build community

- Vault opens door to local history

- Plenty of help organisations in times of need

- Oddities beneath the floorboards

- Tales of a winning cricket team

- Di’s QSM for services to community and environment

- Rewi’s story one of adversity in old Ōtaki

- Urban designer poses critical question - What’s the plan for Ōtaki?

- New road evokes memories of apples and steam trains