This last month the weather was more turbulent across the country than usual. And, despite the red warnings, workers in Aotearoa New Zealand were walking off the job, taking part in the biggest strike this nation has seen for some time.

The economic climate is one of gloom, rising unemployment and living costs, as well as being at the mercy of the toying with international exports and inflation by one of the largest influences internationally. The threat of another world war is not out of the question, either.

And we have been here before. Numerous recessions have occurred in my lifetime, but thankfully, not the Depression that was the result of a very similar chain of events in my parents’ generation.

The Depression in the 1930s in this country was a brutal one. Nowhere in the country was spared, including Ōtaki. Triggered by the 1929 stockmarket crash in the United States, by 1930 the economy here was shattered. Unemployment rose steeply, no one wanted our goods, and imports became unobtainable and unaffordable.

For Ōtaki and the surrounding regions, jobs on the farms and market gardens, and in services that supported them, bore the brunt of the steep decline. Relief work was available for some, but not all, and that work was backbreaking.

Two relief schemes were established here, both in the Te Horo area. In her article in the 1979 issue of the Otaki Historical Society’s journal (issue 2), Kath Shaw notes:

“When export prices dropped and farmers’ income suffered as a consequence, a chain reaction set in that affected everyone in Ōtaki. Business declined and jobs grew scarce. By 1931 there was no seasonal work available.”

At that time there was no unemployment benefit and as demand grew, various relief committees were set up to support those who could find some work, with subsidies for their employers. This included work for Ōtaki Borough Council, which used the labour to “construct the beach frontage with spades, shovels and wheelbarrows, to plant 8000 trees at the Health Camp and to raise a stopbank at the Ōtaki River by means of sand bags”.

But it wasn’t just physical hardship faced by those men. Kath Shaw also notes: “For a man accustomed to pay his way, a woman trying to feed and clothe her children on a pittance, there was a feeling of degradation and isolation, even when they realised that their situation was shared with thousands of people from all walks of life, skilled tradesmen, teachers, lawyers, doctors and businessmen.”

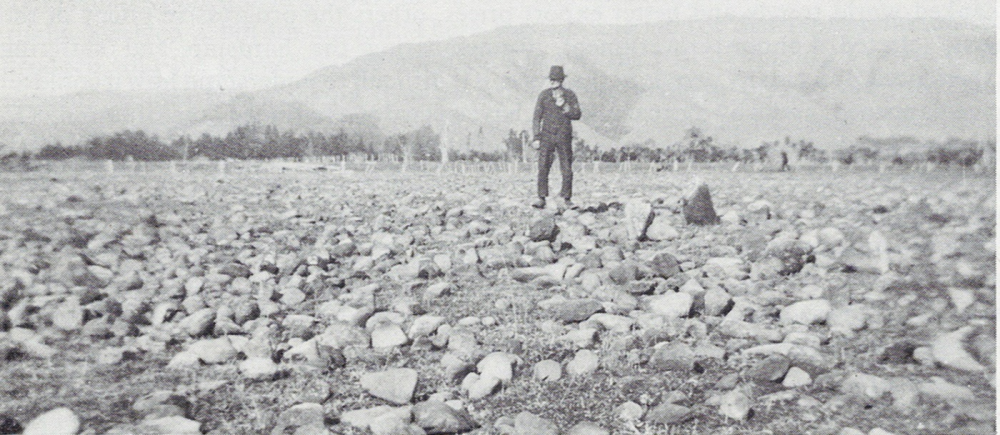

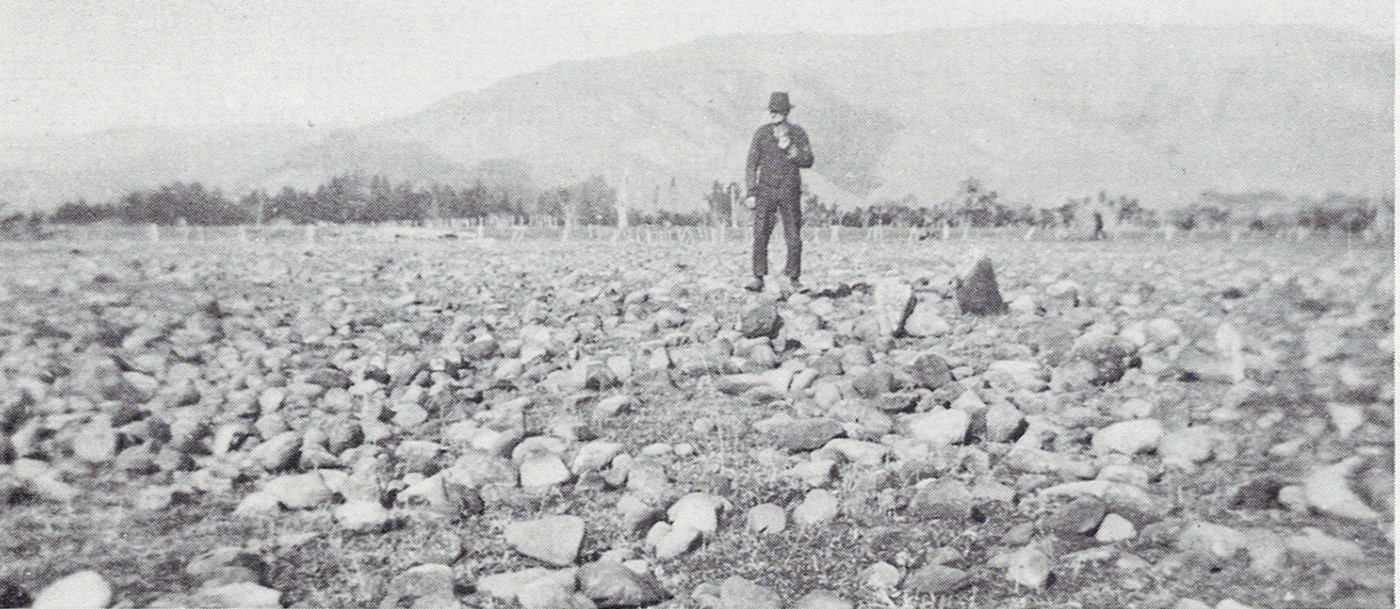

One of the relief camps was in Shield’s Flat, a narrow elevated alluvial terrace about 13km up Ōtaki Gorge Road in the Hautere area. Now an historic reserve established by the Department of Conservation, the area was once used for milling and farming. A significant feature of the reserve is the complex of stone walls and pig-pen structures the relief workers built.

They were built by hand from stones washed down the Ōtaki River that had scattered, over time, across the area. The walls were constructed with smaller stones in the centre, with larger stones creating the “shell” of the structures. The fact these structures are still intact is testament not just to the design, but also to the hard, grinding and ongoing work of the men.

Lower down the gorge is Duggan’s Bush, one of the remnants of the original vegetation covering the river terrace that forms part of Greater Wellington Regional Council’s Key Native Plan for the area. In private ownership, the remnant is one of four within proximity to each other on the south side of the river. The others – Tom’s or Ainslee Bush, Lumsden Bush and Davis’s Bush – are slightly farther away from the river. Within the Duggan’s Bush remnant there are piles and walls of stones collected and stacked by relief workers.

The Hautere Work Scheme provided employment to about 80 men who were housed in tents nearby on a site on the Old Hautere Road. The men, who were paid ten shillings for a six-day week, eventually cleared an area of 3000 acres of local farmers’ land over several years. The farmers themselves were charged per cubic yard of land cleared of stones that became known as “Hautere Turnips” in the process.

It’s believed that the piles have remained owing to the geological nature of the stones. While some were used for other purposes such as drainage, as well as for seawalls and river groynes, the greywacke composition was too soft for roading or other infrastructural purposes. So, they remain as memorials to a difficult time and the heartbreaking circumstances in which they were created.

Despite the inclination of some politicians, workers here have not yet descended to breaking rocks to earn a pittance. But there are parallels in the fall-out of recent global and national policies. The imposition of tariffs on our exports, and our reliance on the global markets, threaten producers in this country. The attacks on the public sector sees our once glowing social support agencies crumbling.

Deliberate strategies threaten peace and democracy across the world and rumblings of another world war become louder. The climatic turbulence sends rocks down our rivers and once again, uncertainty in our minds. The rock walls have stayed secure and strong – hopefully we will, too.

• Nicky is a former journalist with an interest in local history.

OTHER STORIES